LLANBADARN CHURCHYARD by A W GILBEY

CHAPTER 3. BURIALS CUSTOMS AND SUPERSTITION

Death has always been associated with mystery so it is not surprising to find that over the centuries numerous superstitions and customs have become associated with the death of an individual. Certain of these are, of course, universal but a number are unique to the people of North Cardiganshire, the area once contained within the parish of Llanbadarn Fawr.

The earliest burial places were the cromlechs, tumuli and barrows which are fairly general in this region. Indeed there is a connection between these ancient burials and Llanbadarn Church for in 1869, during restoration work at the Church, a large quantity of human bones were found directly beneath the flagstones. Apparently these bones were recovered when the new road from Aberystwyth to Machynlleth was driven through Carn Maelgwyn, a barrow near Penygarn Chapel, Bow Street, and were then conveyed to Llanbadarn, in cartloads, for reburial.

It was the practice for burials before the Seventeenth Century to be made with the corpse wrapped in a shroud because coffins did not come into general use until that time. The Welsh were particularly keen on oak coffins though the poorer people accepted elm as a cheaper alternative. It was usual to dress the corpse in the best clothes of the deceased and cover it with a white shroud before placing it in the coffin. Some parishes had a special coffin, the parish coffin, for the burial of paupers and others who had made no arrangements to cover the expense of their funeral. The corpse would be placed in the grave in the parish coffin which would be retrieved after the departure of the mourners.

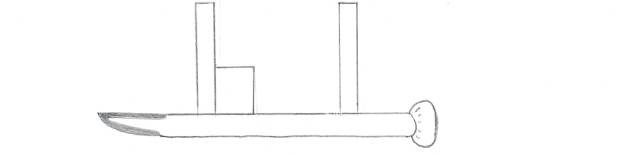

When Llanbadarn was the centre of a large district, especially during the late Eighteenth and mid-Nineteenth Centuries when lead mining prospered, there was some difficulty in bringing the coffins to the Church from outlying districts. The hills and mountains proved difficult terrain for a cart so the problem of conveying the coffin was solved by using a sledge. The contraption designed and used at Llanbadarn until the mid-Nineteenth Century was built of wood though the end of the shafts were shod with iron to protect the wood from wear.

The coffin would be placed in the bier with the feet to the front and the other end resting on the box at the rear.

The men would then lift up the knob end until the bier rested on its iron shod runners and then they would pull the bier down the trackless hills and across country lanes to the Church for burial.

In an age filled with superstition it is not surprising to find that many of the people of Llanbadarn Fawr believed in the death portents then current. Perhaps the most common, and one still deemed credible by the credulous, is the Canwyll Corph' or corpse candle. According to tradition this was a pale light moving slowly above the ground and following a route from the house of a ding person to the Churchyard. Sometimes it was supposed to be possible to recognise the dying person from the sceptral representation carried in the flame. As a general guide if the corpse candle glowed with a reddish tint it indicated the death of a man; a white glow indicated the death of a woman and a faint light indicated a child. If two corpse candles were seen at the same time this was taken to indicate that two deaths would occur in the same household at about the same time. If the corpse candle was seen early in the evening this indicated that the death would take place within a few days; if seen late in the evening then the corpse candle gave notice that the death would take place sometime in the future.

There was also a belief in the 'Deryn corph' or death bird as a death omen. Apparently the appearance of the little grey bird at the window of a room in which a sick person lay was an omen of death: it would flap its wings vigorously against the pane . T he deryn corph might have found its antics a little less alarming in the Ponterwyd area were the custom was to open the windows in the room of a dying person in order to facilitate the escape of the soul.

There were a number of apparitions that apparently foretold death of which the most common in North Cardiganshire was the Teulu (or Toili), the phantom funeral. The teulu took the form of a funeral procession which followed a route from the house were a death was to occur to the Churchyard. The procession would be composed of the mourners and at its head would be the pall-bearers carrying the coffin. Although sceptral it was supposed to be possible to recognise individuals in the procession. A similar apparition, the 'lledrith - wraith', usually appeared at the same time as the person featured in it was dying. The story of. a young French sailor makes an interesting; example of a lledrith - wraith. This sailor arrived at Aberystwyth in the 1840's and fell in love with a servant girl who, by all accounts, returned his affections. He had to return to sea but promised to return. One night the young maid heard her name being called as she prepared for bed and looked out of her window. There she could clearly see her beloved reaching out to her but before she clasp his hand he disappeared. It was a few days later that news reached the town that the French ship had been lost, with all her crew, off the coast of Spain.

Strange noises, rappings, knockings and other sounds were known as 'Tolaeth' and also foretold death. The noises were of a wide character but their persistence and illogical nature were sufficient to worry the superstitious; and it was not just strange noises - the sound of footsteps or even a carriage approaching, when none materialised suggested death. More harrowing; perhaps was the Cyhyraeth ' or death sound, a mournful wailing; or moaning sound said to be emitted by a death spirit, which was never seen, before death. More frequent, but no less harrowing as a death sound was the howling of a dog, the 'ci - yn - udo'. If the dog was close enough to be seen the location of the death could be estimated by looking at the direction the dog faced. The same sort of belief was attached to a cockerel crowing at midnight.

The 'Gwrach y Rhibyn' was a sinister death portent for she was an ugly old hag, with a face as inviting as death itself, skeletal, with long flowing hair and glaring eyes; her ear-piercing shriek foretold misfortune and death though she restricted her visitations to the wicked.

It was the custom that funerals were public affairs and it was expected that each household would send at least one representative to pay their final respect to a neighbour, who, in many cases, would also be a relative. The censure of village gossip was sufficient to ensure the necessary attendance. The date and the hour of the funeral was publicly announced and, if necessary, a man was sent around the district to ensure that everyone knew the arrangements. In Aberystwyth, when a burial was to take place in Llanbadarn, it was the custom, at the request of the bereaved family, for the Bellman to go around the town ringing the Corpse Bell . He would walk along in the early afternoon and, every dozen steps or so, would stop and ring out one solemn stroke on his bell. The custom of ringing the corpse bell probably began as a way of signalling the approach of a funeral though the original use was as a means of banishing the devil and, as such, its use had been banned in 1571. It survived in Aberystwyth until the beginning of the twentieth Century despite a campaign by the Cambrian News to abolish it. Gibson, the editor, wrote in 1870:

In Aberystwyth the Funeral Bell is still tolled solemnly round the town on funeral days. When the dead

had to be carried on to Llanbadarn, or Baptist or St Michael's Churchyards, it may have been necessary

in order to get carriers, but now, with horse hearses, it is not necessary. The large gatherings at funerals are

anything but indications of respect and do not conduce to the solemnity of the occasion.

The night before the funeral was the'Gwylnos.' or wake night and it was the custom to hold a prayer meeting in the room were the corpse was lying. It was traditional to use the occasion to refer to the good character of the deceased. Friends at the gwylnos would be expected, on entering the room, to kneel by the coffin and say an appropriate prayer, such as the Lord's Prayer. It was also the custom that friends of the deceased would bring some little gift to console the bereaved family. The gifts could be of butter, cake, tea, gingerbread or sugar and they were accepted by a member of the family specifically placed at the front door. He would accept the gift saying “Diolch a cymerwch attoch”. The guests would then be shown into the kitchen where the bereaved family would have put on a meal of bread, cheese, wine or beer. The giving of beer at funerals was quite common in the early Nineteenth Century, but the sober Victorians frowned upon the custom and it was abandoned. It was probably for this reason that the Welsh gwylnos was never as rowdy an affair as the Irish wake. In some households it was the custom to watch the coffin overnight before the funeral and sometimes this duty was performed by the youths who took the opportunity to do some drinking or even some courting.

The day of the funeral began with a meeting of the mourners at the home of the deceased at which there would be feasting. Important guests would take it in turn to arrive and sit at the main table while, for the less important, stools would be placed around the main room and outside the house. After the food a short service was conducted at the house and then the coffin was carried out of the house by the closest relatives. The men would carry the coffin in teams of four (sometimes helped by women) to the Church. In The Welshman of March 1842 there is the following report:

It is well known that the Welsh differ from the English in the manner of carrying their dead to the long home.

While the latter are borne either by strangers, generally paid for the purpose, the Welsh are always carried

by their nearest and dearest relatives. An affecting instance of this occurred last Friday at Llanbadarn Fawr

were Mr John Hughes of Cefnhendre, aged 80, was carried from the Church to the grave by his eight sons -

the youngest of whom succeeds to the paternal homestead, according to the ancient Welsh custom. (See D206)

Coffins from outlying districts were brought in on a special sleigh bier or on the ‘elorfach', a horse bier. This consisted of a pair of long shafts fixed at either end to the saddle of a horse and tranversed by pieces of wood across tile central part which bore the coffin.

When the procession was formed it set off at walking pace for the Churchyard. At the start of the Nineteenth Century hymns would be sung along the way, and especially when passing a house, but this practice was abandoned later in the century. The funeral procession would be met at the Churchyard gate by the clergy and led into the Church. There the coffin would be placed in front of the altar, supported on small stools. At the start of the Nineteenth Century it was the custom at Llanbadarn for members of the deceased family to kneel around the coffin and pay their respects, but this custom, too, was later abandoned.

After the Church service the coffin was carried to the place of internment and lowered into the grave. At the close of the service one or two hymns, favourites of the deceased, were sung. Before the mourners left the graveside it was the custom to leave a silver piece, 'spade money' (arian y rhaw), on the blade of the gravedigger's spade. In the Seventeenth Century it was the custom to throw a sprig of rosemary, symbol of fidelity, into the grave but by the Nineteenth Century this had been replaced by the placing of flowers above the grave. It was customary to decorate the graves with flowers on Palm Sunday (Sul y Blodau or Flowering Sunday) but this practice was also abandoned.

Yet another custom which suffered the same fate at about the same time and which was well practiced at Llanbadarn is expressed in the following couplet

Claddwch y meirw

A dewch at y cwrw.

(Bury the dead and come to the beer.)

St Padarn's Church and the Black Lion