LLANBADARN CHURCHYARD by A W GILBEY

CHAPTER 2 THE PARISH AND THE PARISH REGISTER BOOKS AT LLANBADARN FAWR

The parish of Llanbadarn Fawr was once the most extensive in the Principality, covering most of North Cardiganshire though, during the Nineteenth Century, but it was gradually reduced in size. The parish is now composed of most of the two districts of I ssayndre ('below the town') and Uchayndre ('above the town'), which formed the nucleus of the ancient parish. The parish boundaries are, it seems, gradually being reduced by the expansion of the town of Aberystwyth and its satellite residential areas; until 1861 though, Aberystwyth was part of the parish of Llanbadarn Fawr.

It is generally agreed that the Church of St Padarn was built on its present site at the beginning of the Thirteenth Century and that some monastic buildings stood on the same site for centuries before the Church was built. As is to be expected no formal parish records were kept until they became required by law. In 1538 Thomas Cromwell issued instructions, known as Cromwell' s Mandate, that every parish had to purchase a ‘sure coffer', a stout box with locks, to act as the parish chest in which all parish records could be kept. The Vicar held one of the keys to the parish chest and the other was held by a Churchwarden. Cromwell also instructed the ministers to enter into a book all christenings, marriages and burials in their parish; this was to be done after each Sunday morning service in the presence of a Churchwarden, and the book was to be safely kept in the parish chest.

A few parishes immediately complied with the 1538 Mandate but most did not; instead it became the practice to record the information on pieces of parchment or paper and these were kept, rather erratically, in the parish chest. To remedy this situation the 1598 Provincial Constitution of the Clergy instructed the clergy to keep the records in parchment books. It also instructed the clergy to copy into these register books the records kept since 1538 and especially those entries made since the accession of. Queen Elizabeth I in 1558. The Churchwardens were instructed to witness all entries and to ensure that they were read out at the main Sunday service. In addition the Churchwardens were to transcribe the entries made in the Register Book at Easter each year and send the transcript to the diocesan registry; these copies are known as the Bishop' s Transcripts and provide a useful source of information, especially where the original registers are missing. Most parishes immediately followed the instructions, even if they took 1558 as the starting date. The parish of Llanbadarn Fawr would have been no exception but, unfortunately, none of the early registers have survived.

The surviving register book at Llanbadarn Fawr begins in 1678 this may be a reflection of' the Burial in Wool Act of that year. Parliament had passed a similar Act in 1667 which declared that, except in cases of plague, no corpse should be buried "in any shirt, shift, sheet or shroud or anything whatever made or mingled with flax, hemp, silk, hair, gold or silver, or in any stuff or thing, other than what is made of sheep's wool only." The Act was designed to help the woollen industry. To ensure it was complied with a written statement was made at each burial and it was a simple matter to maintain the register at the same time. Failure to comply with the Act carried a penalty of a £5 fine on the estate of the deceased and on others connected with the burial. The Acts were strictly enforced for a number of years after 1678 but had fallen into disuse long before their repeal in 1814.

The Register Books at Llanbadarn were poorly kept; they are frequently incomplete and many years are totally unaccounted for. It is not until the early years of the Nineteenth Century that the Registers begin to present an accurate picture of the parish. The earliest Registers were written up in Latin but this practice was stopped in 1733. In the Llanbadarn Register is this entry:

Note that Hence forward we are oblig'd by Act of Parliament to keep our Register Book in English, the year 1733.

In the majority of instances the keeping of the Register Book was the responsibility of the Curate of the Parish, and it is clear that some curates were more conscientious than others in performing their duties. An entry of 1752 indicated that the Register was incomplete because "The Curate did not regularly keep the register.”

The Register Book recorded on October 3rd, 1783, that: A duty of 3d upon every burial. Act of Parliament commenced 1st of October 1783.

This was a result of the Stamp Act of 1783 which imposed a duty of 3d. on every entry in the Register, be it christening, marriage or. burial, in order to raise monies to pay for British involvement in the War of American Independence. The Vicar of the Parish was charged with the collection of the duty and was allowed to keep a commission of 10% to cover his expenses. Perhaps it is coincidental but 1784 was a record year for burials at Llanbadarn Fawr with 221 burials, three times the average number of entries.

In 1812, as a result of George Rose's Act, Llanbadarn had to adopt a separate register each for baptisms, marriages and burials. These registers were specifically printed for the parishes by the King's printers and provided sufficient space to record the name, age, address and occupation of the deceased. These registers remained in use throughout the Nineteenth Century and were augmented by the introduction of death certificates from the 1st of July 1837. The death certificates, collected by the General Register's Office, provide details as recorded in the Register, plus the cause of death. Some of the entries in the early registers are given here to indicate their nature:

June 10 1772 Sailor drown' d at Aberystwyth Harbour

August 25 1772 A child from the Turnpike Hous.

April 30 1773 Woman died at House of Correction

Octr 12 1776 John Jones, stranger

Octr 2 1782 William Roderick - Drowned

Octr 14 1784 Thomas Jones, Aberystwyth, Tidewaiter

April 13 1785 Evan Jenkin, pauper

September 15 1785 Morgan Jones, de Nanteos, Huntsman

Septr 7 1787 J John Jones, Esqr, Collector of the Customs, Aberystwyth

March 31 1812 Three strangers drowned at Wallog

April 3 1812 Another stranger drowned at Wallog

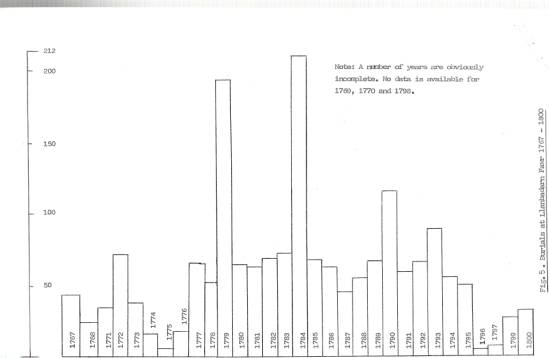

Although the Eighteenth Century registers are of limited value because of the casual manner in which they were kept they do provide some information and raise a number of interesting questions. A substantial number of entries are known to be missing but the overall picture is one of burials amounting to about 64 per annum on average except for the three peak years of 1779, 1784 and 1790. Obviously some factors were at work to create these peaks which are clearly cyclical in nature. On examination it is clear that, after a peak year, the number of deaths recorded declines for a year or two before beginning to build up into another peak year. The graph below demonstrates this phenomenon. It would be very difficult to find the cause of these cycles but it clearly must be related to the agricultural practices and weather conditions of the late Eighteenth Century.

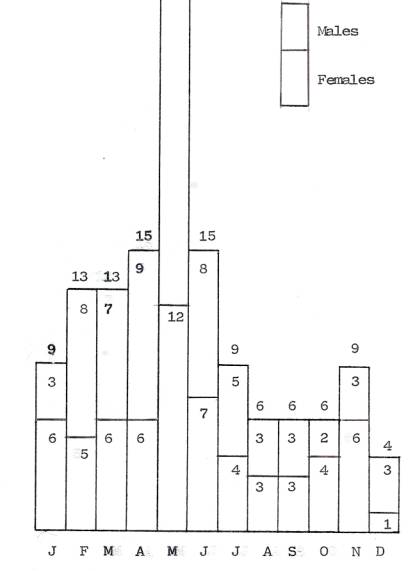

The same phenomenon is evident in the early years of the Nineteenth Century, with the peaks concentrated around 1810 - 1814, 1818 - 1819, 1826 and 1833. It is known that the years of the early decades of the Nineteenth Century were very difficult for the agricultural workers of Wales. The changes brought about by the Agricultural Revolution caused great hardship to the tenant farmers while the high price of grain, resulting from shortages during the Napoleonic Wars and the Corn Laws which followed, must have led to conditions close to famine, especially in years when the harvest failed. Why this should lead to a peak in 1833 is not clear but, on closer examination, it may be possible to offer some suggestions. In 1833 most of the deaths occurred in the first six months of the year as can be seen in the graph below showing the number of burials each month at Llanbadarn in 1833

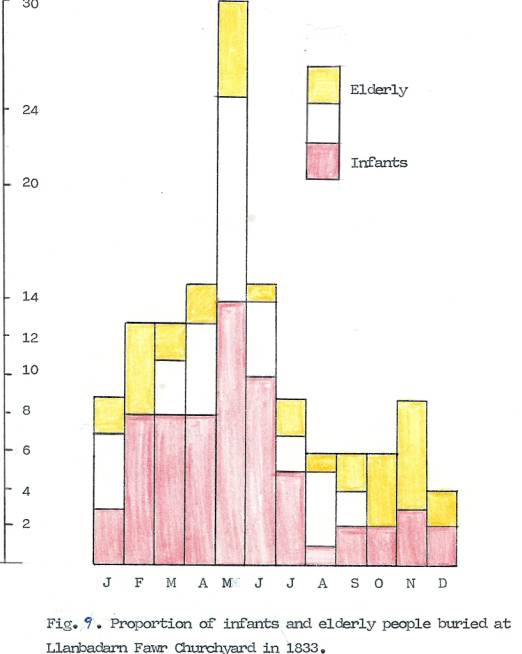

This was the time in agricultural communities when the danger of famine was greatest. The previous year's harvest was being consumed and fresh foodstuffs were not yet available. Even if there was no famine it is clear that the strength of individuals would be weakest during this period and thus they would be more susceptible to the ravages of diseases. It is clear from previous studies that in times of famine or epidemics the youngest and eldest die first and this trend is evident in the 1833 mortalities:

he evidence increasingly points to some form of disease, probably typhus, influenza or cholera, being responsible for the high number of deaths though there were, of course, a variety of infectious diseases capable of decimating a population.

One of these pieces of evidence comes from the fact that some children from the same family died within a short period of each other. At Penrtliw Farm David Jones died on March 7th, aged 2, a month after his sister Ann, aged 7 months. At Penbont, Llangorwen, Mary Davies, aged 2, died on February 23rd, to be followed nine days later by her four year old sister, Jane. An examination of the places of residences of the deceased seems to suggest that the entire district was affected and this would tally with an infectious fever. Figure 10 shows the distribution:

Farms in the parish 54

Aberystwyth 26

Llanbadarn village 18

Waunfawr 5

Tafarn 4

Gwar-y-felin 4

Llangorwen 3

Llangawsai 3

Pwlhobi 3

Commins 2

Penparcau 2

Rhydyfelin. 2

Tynyllidiart 2

Bow Street 2

Chancery 2

Clarach (Ysgoldy) 1

Llanrhystud 1

Lovesgrove 1

'Nanteos Arms' 1

Rhydfirian 1

Fig. 10 Places of abode of the deceased buried at Llanbadarn Fawr 1833.

The year 1833 also marks the peak of baptism at Llanbadarn Fawr and this could reflect the natural concern of parents wishing to baptise their child in the face of an epidemic. That there was an epidemic is evident from the newspaper reports of the period; the 'Cambrian' of June 1st, 1833 reported:

The influenza still prevails in different parts of the Principality; but it has, in general, greatly abated.

A week later the same newspaper reported:

The influenza still continues to lay up several persons at Carmarthen and neighbourhood. Indeed there is scarcely a house but some of its inmates are affected. We have not heard of any deaths from its effect, though the sufferings of some persons have been most severe.

The Cambrian may not have heard of any deaths from the influenza but the Register clearly demonstrates that there were deaths in this area reaching a peak in May 1833. One possible explanation for the influenza was Asiatic Cholera, an epidemic of which struck Europe in 1830 . The cholera was imported by sailors into Sunderland in October 1831, and was first recorded in North Wales in May 1832 and by July 1832, had been recorded in Carmarthen. The disease could have been brought to Aberystwyth by sailors and ravaged the area around in the spring of 1833 before burning itself out.

The Registers for the remaining years of the Nineteenth Century records an increase, on average, of burials at Llanbadarn in each passing decade until the 1870's. This reflects the expanding population of the town of Aberystwyth and its hinterland, the lead mining areas, which were served by the Church at Llanbadarn until new parishes, and new churches were created. The years after 1870 therefore saw a decline in burials at Llanbadarn and this was accelerated by the opening of the Plascrug Cemetery at Aberystwyth and the partial closure of Llanbadarn Churchyard in 1881.