LLANBADARN CHURCHYARD by A W GILBEY

CHAPTER 1. THE CHURCH AND THE CHURCHYARD

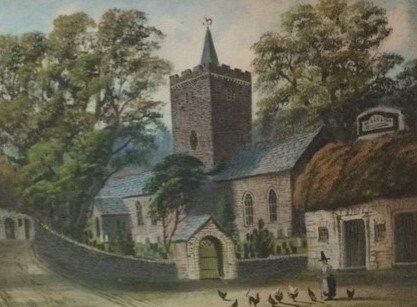

St Padarn and the Black Lion - details from a painting by Worthington owned by the author

The history of Llanbadarn Fawr, as Professor Bowen has so ably demonstrated, predates Christianity but it is to a Christian settlement, founded by St Padarn, that the village owes its existence. St Padarn' s Sixth Century monastic settlement was probably located on the site of the present churchyard; it was oval in plan, protected by raised earth banks and consisted of a number of buildings ranging from individual beehive cells to a large church built of' wattle and daub. In later centuries the monastery was reconstructed in stone and parts of these buildings were seen during the Nineteenth Century.

It is tempting to see the 'llan' of St Padarn's monastery in the present shape of the Churchyard. The Gogerddan estate map of' 1797 showed the churchyard to be an elongated (roughly equal to Sections A, C, H, J and half of B on our plan), very much the traditional shape of an early Celtic monastic site. The churchyard was extended during the first half of the Nineteenth Century for the Tithe Map of 1846 shows the present shape of the churchyard covering an area of' about two acres.

Although it is not clear when the practice of burials within the 'llan' was begun in the Celtic Church it is presumed that it predated by two centuries, the introduction of the same practice into the Augustinian Church by the Archbishop Cuthbert in 750 AD. It is probable, therefore, that the Churchyard at Llanbadarn was first used as a burial ground by the followers of St Padarn; it stayed in continual use until the late Nineteenth Century when it was closed for general burials though internments contint1ed to be made, the last in 1979 .

The present church was begun about 1200 and has undergone a number of changes; nevertheless it is fundamentally similar to its ancient design. Richard Pococke, travelling through Llanbadarn Fawr on August 20th, 1756, reported that "The church is in the shape of a cross, with a tower in the middle. There are no marks of very great antiquity about it. There are stalls in the East (Chancel) which is a common thing in Wales. And on each side of the East window is a common monument shut up in a cupboard so as to preserve it from dust.” It appears that to the north of the present building, at the turn of the last century, were buildings which bore the 'marks of very great antiquity' for Meyrick, in his 'History of Cardiganshire', considered that they were "probably a part of the old monastery, a pointed arch, and other circumstances in them, indicating great antiquity.”

In the area described by Meyrick the earliest grave dates from 1818 so it is fair to assume that it was about then that the area was cleared of the old buildings and used for burials. The practice of clearing the churchyard of memorial stones from previous generations was well established at Llanbadarn. In 1818 the Vestry Books record that £1.10.0 was spent in building a charnel house where bones, disinterred in the course of new burials, could be deposited. Most of the memorial stones were then broken up to use as filling by the contractors and carriers contracted to remove them; others were used as building material. In our survey we came across only one example of a memorial stone being re-used to record another death (see J158) but there were numerous examples of stones being used for other than their original purpose in the churchyard. By the chancel door, for example, are two stones used as a step. One of these lies upside down and the inscription should prove readable but the inscription on the other has been rendered illegible by the passage of' time and countless feet.

The churchyard, because it was never laid out nor properly planned as a place of burial, has an untidy but not unattractive appearance. However there is a long history of complaints regarding the state in which the churchyard was maintained despite the efforts of the Vicar and the Churchwardens. In 1866 a visitor to the Church wrote in protest to the Aberystwyth Observer complaining about its disgraceful state:

“I do not allude to the tombs, which, of course, should be kept in repair by those to whom they belong; but I speak of

the ground of the churchyard, of the nettles, weeds and rank grass, which are knee deep and foul beyond

description.”

More serious than the problem of keeping the churchyard tidy was the problem of maintaining the structure of the Church and the Churchyard wall. The former was only resolved by the extensive restoration work carried out in the two decades from 1861. The latter problem was never satisfactorily tackled and a section of the wall would be re-built only when close to collapse, or after it had collapsed. In January 1864, for example, a section of the wall overlooking the road collapsed as this extract from a local newspaper proves: “On Saturday last, in consequence of the wet state of the ground, caused by incessant rain, a portion of the churchyard wall above the road at Llanbadarn, gave way to an extent of some four or five yards, exhibiting to view the coffins, as we are informed, of the slidden graves adjoining.”

In addition to the above problem it was clear that the churchyard, by the middle of the Nineteenth Century, was overworked and rapidly becoming a health hazard. It was this that led, in the years following the Public Health Act of 1875, to demands that the churchyard be closed. In 1876 diphtheria mysteriously originated in the village and ravaged the district for 13 months. A link was established between the disease, the overworked churchyard and the water supply (at the time all Llanbadarn's water came from wells and springs) and the Cambrian News, through its editor, John Gibson, (later to receive a knighthood) took up the campaign to close the churchyard. Gibson wrote, in June 1878:

This burial place is one of the oldest, if' not the oldest in Wales. There is not one inch of the old part where human remains cannot, be found. When a grave is opened, bones are thrown up freely. The Vicar has no power to interfere, and people prefer to bury their dead in family graves. Now the time has come when a very large portion of the old churchyard at Llanbadarn should be closed. Sentiment may say "No" but sentiment also says "Yes" and public health "Yes” too. This is a public question, and an old man may be excused for suggesting that a graveyard that has done duty for eight or nine hundred years may be closed with advantage.

The Cambrian News was supported by the Sanitary Inspector for Llanbadarn, David Jones, who reported to the Rural Sanitary Authority "the ancient part that :immediately surrounds the building of L1anbadarn Church may well be considered as a highly consecrated mass of' human remains" and asked that the Authority approached the Vicar to close the Churchyard.

The Vicar, John Pugh, and the Churchwardens, denied that the churchyard was a health hazard but accepted that it was near saturation point.' They would agree on the churchyard being partly closed but reserved the right of those families who wished, and where there was space, to continue burials in family graves: in effect this prevented new burials from Aberystwyth and from families coming into the village. This compromise was accepted and the churchyard closed in November 1881 though families continued to use the churchyard regularly for the rest of the Nineteenth Century. It was only natural that the people of Llanbadarn Fawr, after a thousand years of use, should wish to bury their dead in the village churchyard. The following poem, written by a man Llanbadarn, in 1864, suggests the feeling towards the Church and the Churchyard held by many parishioners:

Thou sacred edifice! with vaulted aisle,

And windows from which painted figures smile;

In childhood's happy hours I gazed on thee,

And thy time blacken'd tower looked down on me.

Sweet infant dreams return at moments now,

And youth' s bright flowers are twined about my brow;

Youth's visions fair illuminate my soul,

And,. silver clad, through fancy's regions roll.

Yet when into the future dim I look,

And trace its winding like a limpid brook,

Can I forget the calm and cloudless past?

Forbid it God! while life and reason last.

Oft have sat in thee – a little child

With dreamy thoughts and aspirations wild,

And watch' d the shadows on thy pavement play

Or o'er the tombs of the departed stray -

The tombs of those me in thee loved to kneel,

Who spoke and felt as we now speak and feel –

Who tasted pleasure and partook of pain,

Whose ruby life-blood warm'd each swelling vein.

The soft colours from thy windows rest

Upon the lifeless frame and icy breast

Of one, perchance, who watched them as they strayed

Across the spot where other forms decayed.

O! Sacred structure stranger-steps will sound

In thee, when we have sought our kindred ground -

When we are numbered with the silent dead,

Heavenward still thou'lt lift they aged head.

The Church and the Black Lion by Worthington from a painting belonging to the author